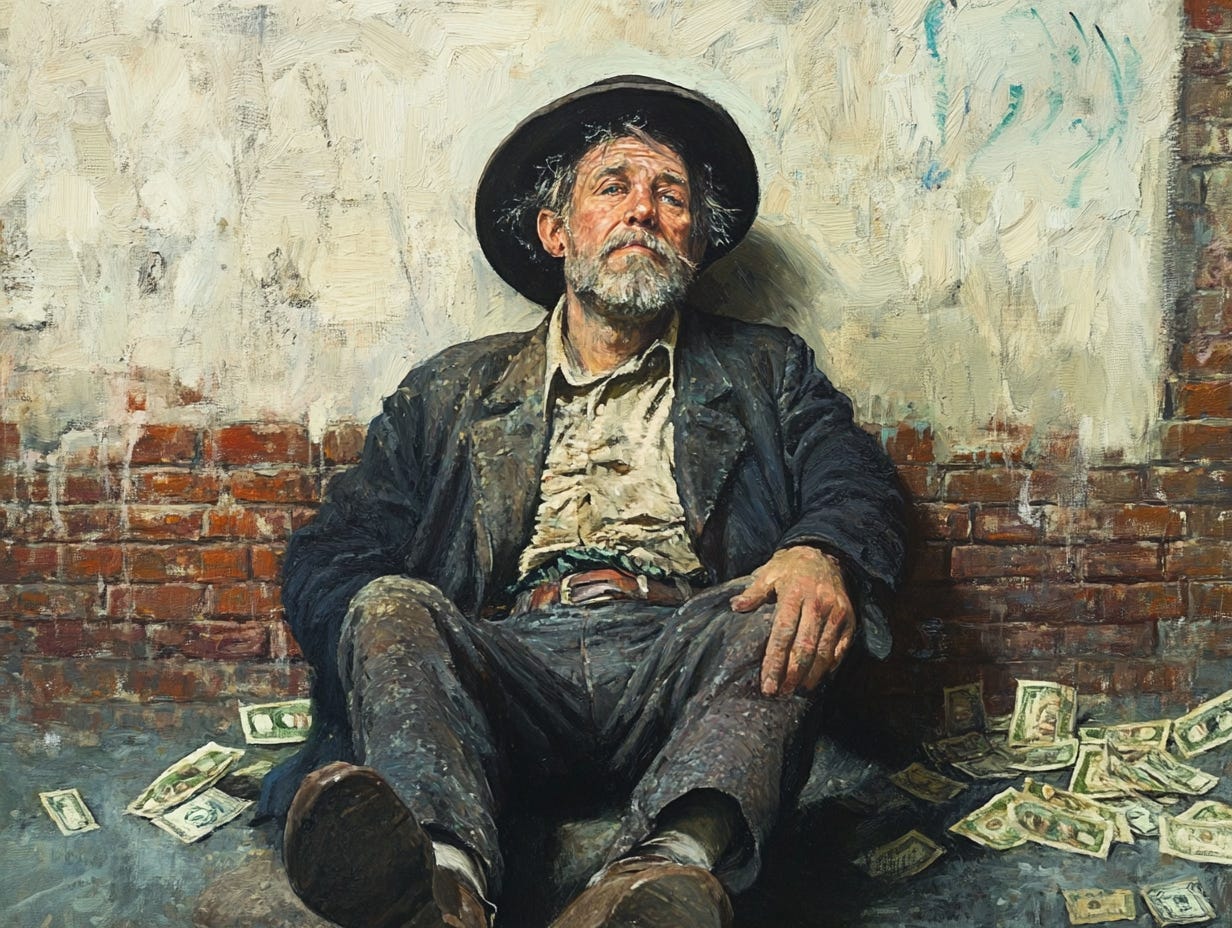

The Homeless Man Does Not Envy The Billionaire

“The homeless man isn’t jealous of the billionaire; he’s jealous of the slightly richer homeless man.” This quote cuts straight to the heart of human psychology, revealing a painful truth about how we measure ourselves: our envy rarely looks upward to the unattainable but sideways to the painfully close. Let’s explore why we compare locally, why it hurts so much, and what it teaches us about human nature.

Proximity Breeds Envy

Why isn’t the homeless man jealous of the billionaire? Because the billionaire’s wealth is an abstraction, a distant reality that doesn’t register as a valid comparison. The billionaire’s penthouse, private jet, and luxury lifestyle are so far removed from the homeless man’s world that they feel fictional.

But the slightly richer homeless man—his peer in the encampment with a better sleeping bag, a sturdier tent, or a warmer jacket—that hits differently. His advantage is visible, tangible, and maddeningly close. That’s the key to envy: it thrives on proximity. We don’t resent what feels unreachable; we resent what feels almost attainable.

This isn’t just anecdotal. Social comparison theory, developed by Leon Festinger, explains how we evaluate ourselves by looking laterally at peers. Instead of comparing ourselves to the far-off billionaires of the world, we look at those in similar circumstances. Their successes feel close enough to touch, which makes their advantages sting more deeply.

The Weight of Small Differences

Relative deprivation theory underscores this idea: dissatisfaction doesn’t come from absolute lack but from perceived inequity within our reference group. The closer someone is to us in situation or status, the more their small gains feel like glaring losses for us.

Behavioral economist Richard Thaler offers another layer to this. His work on “mental accounting” shows how we focus on visible, immediate inequalities rather than abstract ones. For the homeless man, it’s not the billionaire’s wealth that stands out—it’s the richer peer in the next tent, whose advantage feels like a personal slight.

The philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche captured this dynamic with his concept of ressentiment—a deep-seated resentment toward those slightly better off. Unlike the billionaire’s wealth, which feels impossible, the richer homeless man’s position seems painfully attainable. His success becomes a mirror for unfulfilled potential, fueling bitterness and frustration.

Why We Don’t Look Up

Envy doesn’t travel across vast distances. The billionaire is too far removed to elicit jealousy because there’s no emotional connection to their life. Comparing yourself to someone so far ahead is like racing someone who’s already on Mars; it doesn’t feel relevant.

But the man in the next tent? His slight edge creates a sharp, personal tension. It’s a comparison that’s both unavoidable and emotionally charged. His success highlights what could be yours, if only circumstances—or luck—were slightly different.

Social Media: Envy’s Modern Playground

This principle of proximity plays out not just physically but socially. Social media is the ultimate proximity machine, connecting us to people whose lives feel just close enough to ours to spark envy.

We don’t resent celebrities’ curated perfection as much as we resent a friend’s vacation photos, a coworker’s promotion, or a neighbor’s remodel. These are modern versions of the slightly richer homeless man—people close enough to trigger that gnawing question: Why not me?

Lessons in the Trap of Comparison

The homeless man’s plight highlights an uncomfortable truth about all of us. We aren’t wired to resent distant wealth or power; we’re wired to obsess over those just slightly ahead of us. This creates a relentless cycle of dissatisfaction, especially in environments where small disparities are visible and constant.

Breaking free requires rewiring our perspective:

Change the Reference Point: Instead of looking at others, reflect on your own growth. Compare today’s version of yourself to yesterday’s, not to someone else’s.

Cut Down Triggers: Social media amplifies proximity-based envy. Reducing exposure—or viewing it critically—can help break the cycle.

Cultivate Empathy: Instead of resenting peers’ advantages, understand their struggles. Everyone faces challenges, even those slightly ahead.

The Takeaway

The homeless man isn’t jealous of the billionaire because the billionaire’s wealth is too distant to matter. His envy targets the richer man in the next tent because their difference is visible, tangible, and feels achievable.

This is the harsh reality of human nature: envy doesn’t arise from vast disparities but from the narrow gaps that feel within reach. Recognizing this is the first step toward freeing ourselves from the trap of comparison. Because at the end of the day, it’s not the billionaire who haunts us—it’s the person just one step ahead.